|

| July 2019 |

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

It's been a good run – stock tank

Saturday, December 27, 2025

Mandarin tree re-homed

|

| I'll miss her! |

|

| At her new home! |

Wednesday, December 17, 2025

Notes to myself

Two Sundays ago, I collected seeds from some small purple asters that grow outside the front doors of the First Baptist Church in Blanco. I'm not sure of the species. This afternoon, I finally spread them where I think they'll be protected if they germinate. Some briefs rains yesterday and drizzle today should help in that department.

Friday, December 12, 2025

Porcupine!

Earlier this week, James and I drove out to our property northwest of Blanco. On my own I went down a trail. It wasn't long before I spotted something nosing around in the grass.

"Psssst, James," I whispered call to him. Together we watched a North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum). My first one to meet in the wild! As he/she waddled away, I took a short video. So cool!

Monday, December 8, 2025

Very defensive wolf spider

|

| All photos and videos by James Hearn |

Tuesday, October 7, 2025

No second spring

|

| American beautyberry |

|

| Velvetleaf mallow |

|

| Turk's cap |

|

| Lindheimer senna |

|

| Trumpet creeper |

|

| Plateau goldeneye |

|

| Texas lantana |

Monday, September 29, 2025

Tithonia

As a general rule, we try to plant only natives. But I gave in last week and bought six tithonias (Tithonia rotundifolia) from the Arnoskys at their Blue Barn. I've seen how tall they grow there and how they do indeed attract a lot of butterflies. This species is native to Mexico and Central America. We'll see what happens!

Mandarin tree

October 10, 2025 UPDATE – We peeled our last two mandarins. Oh, my! They were sweet, sweet, sweet!

Thursday, September 11, 2025

Small matters

As a general rule, I try not to interfere with nature. But yesterday, I did. I interfered.

After supper, I was in the back yard, walking a path, trimming dead foliage here and there. Along the way, I stopped to admire the last surviving one of five yellow garden spiders (Argiope aurantia) that took up residence this past summer in our yard. At the base of her large orbweb, she'd hung a recent catch, wrapped in white webbing. A couple of little legs dangled out through the silk. When I saw them still moving, I felt sad. That's nature, I told myself, and walked on by.

But I went back.

"I'm sorry," I told the spider. "But I have to rescue this one." Trying not to damage her web too much, I was able to remove the dung beetle – likely a Texas black phanaeus (Phanaeus texensis). I took a picture of her (above), then went in the house for scissors. Could I save her? I had to try.

Patiently and gently, I trimmed fibers and pulled away silk with my fingernails. I was so afraid that I might damage or pull off one of her legs. All the while, the beetle struggled and fought, never tiring or giving up. "You want to live, don't you," I told her. "Well, I'm trying!" Slowly, bit by bit, the silk came away. At one point, I could see that the wrapping could be peeled away. It wasn't sticky at all, just tight.

Miraculously, the spider's webbing finally fell away and off! My beetle friend was free, free, free! I'd done it!

Happy and relieved, I carried her to an open area outside our yard and set her on a rock. Quick as a flash, she buzzed up, up and away! (I barely got a video of her taking off.) Her final mission in life now is to deposit eggs in some poop and then go to heaven. She won't live much longer. That's nature. So was I wrong to interfere? Maybe. But when I saw her struggling and her determination to live, I had to try and help. I couldn't just walk away.

One little beetle – who cares? Me and my heart did. Because small matters.

|

| The strong silk webbing that was around the beetle. |

|

| I hope my spider lady forgave me. |

Tuesday, September 9, 2025

Wrapping up a grasshopper

Take a look at this amazing video taken by Bunnia DoByns of Blanco, Texas. She was there at just the right moment to see a yellow garden spider (Argiope aurantia) catch and wrap wide swaths of silk around a grasshopper that had just bumbled into her orbweb. With Bunnia's permission, I'm sharing her video here and also on my YouTube channel.

If you look closely, you can see how this spider is pulling silk from her spinnerets at the tip of her abdomen. Spider silk is comprised of proteins and is liquid until it hits air. Then it solidifies and becomes super strong and elastic. About halfway through this video, I believe the spider is biting and injecting venom into the grasshopper, which will paralyze and provide a fresh meal for when the spider's ready to eat.

Thank you, Bunnia!

Love to talk about those spiders....

Tuesday, September 2, 2025

Notes to myself

Friday, August 29, 2025

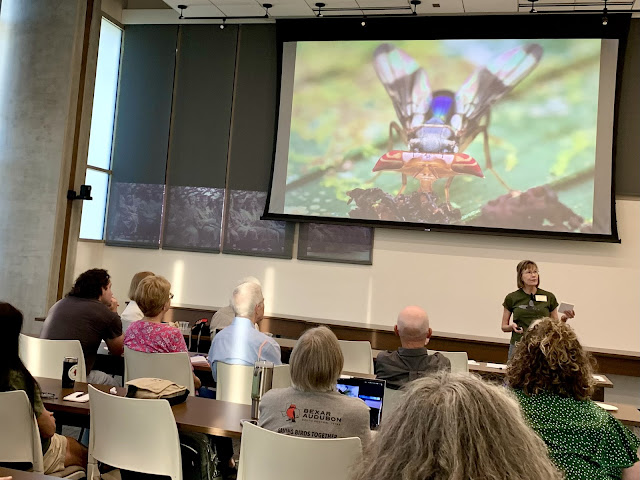

Flies, oh my!

Afterward, members John Huston and his wife chatted with me briefly about their black solider fly larvae, which have taken over their compost bin. During my presentation, I'd briefly mentioned how these larvae are used commercially to recycle waste, make animal feed and even control house flies. At first, I thought they'd purchased larvae to get started. But no, the black soldier flies just showed up and deposited eggs. I asked John if he could send me a photo and video, which he kindly did. With his permission, I'm sharing here.